Dianne Kaufman

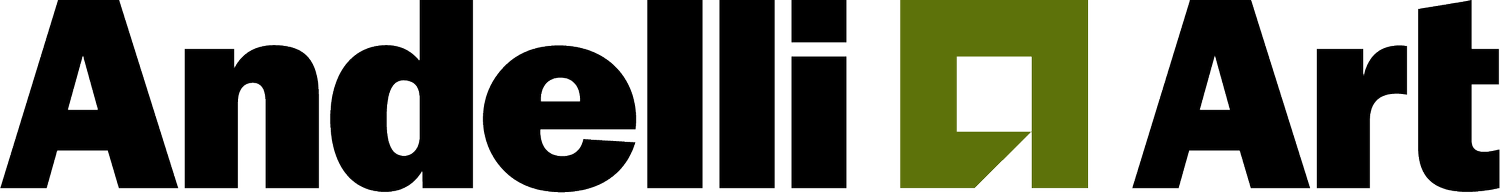

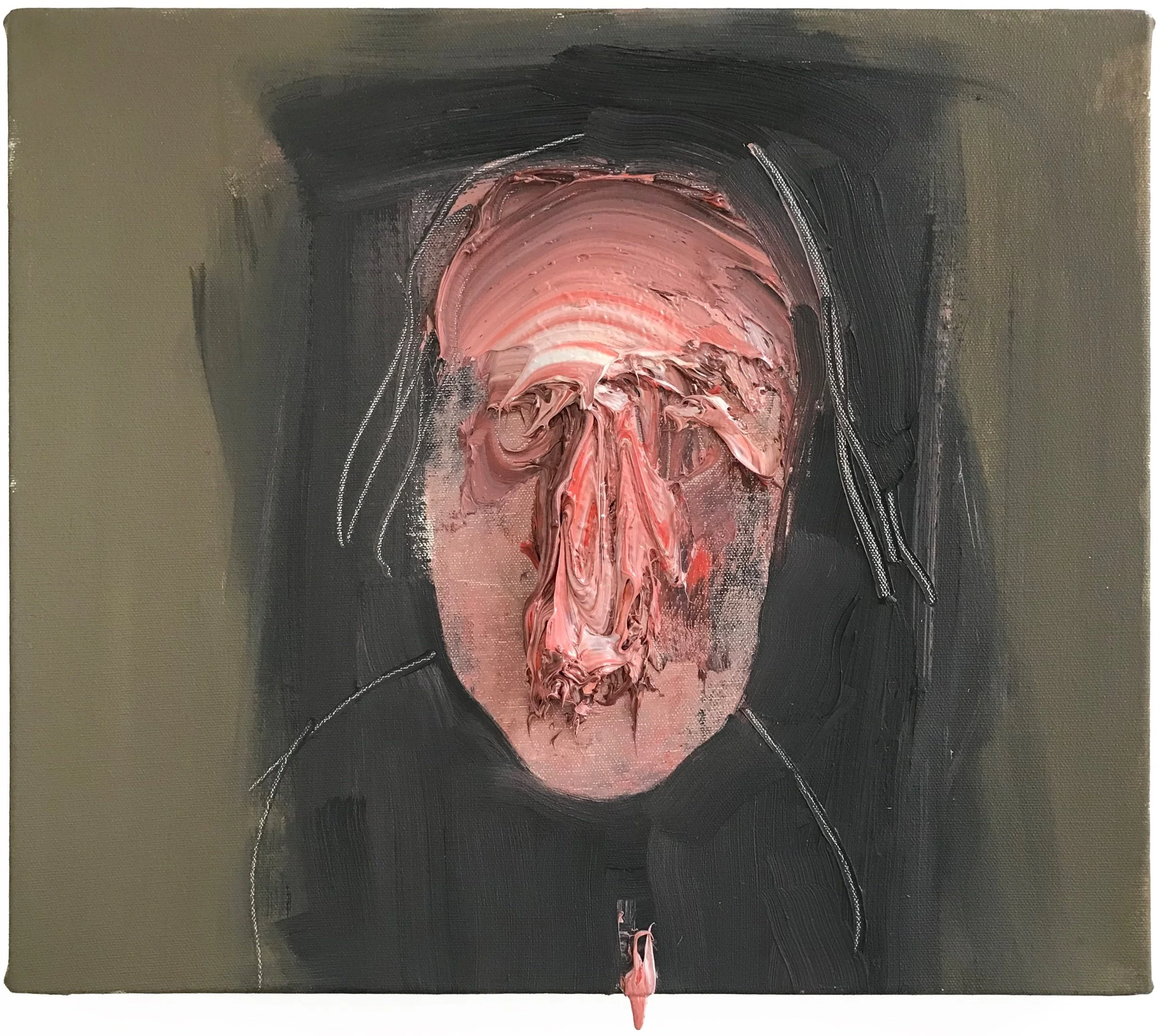

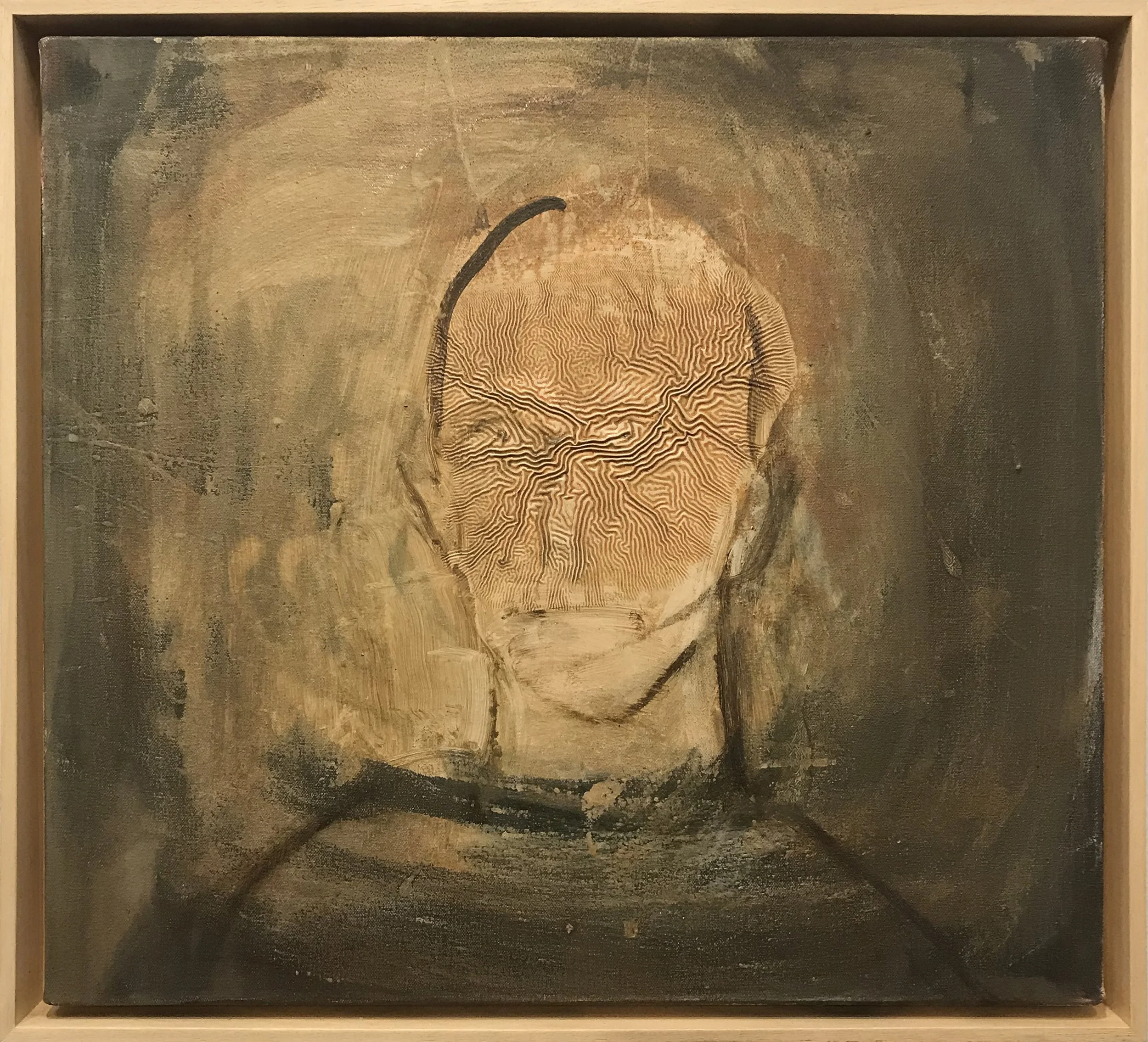

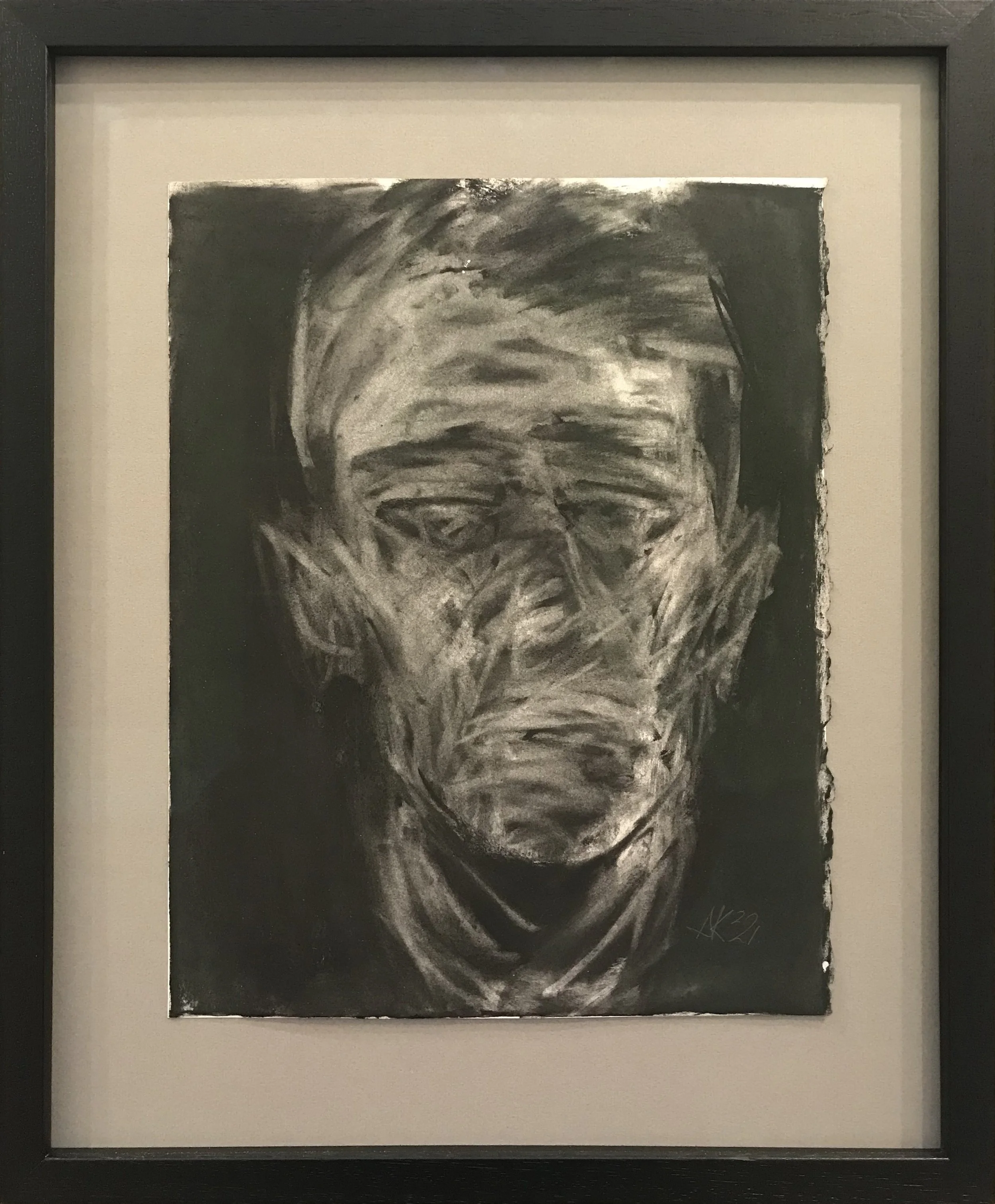

Dianne Kaufman believes in paint. What it can do, physically, washed across or thickly impasted on to canvas, and what it can mean, pushing us beyond the physical into metaphysics and metaphor. Her paintings confound expectation and challenge definition; they are heads without faces, where features shift and vanish under surfaces encrusted with webbed networks of wrinkles like reefs of exotic coral or the exposed lobes of the brain.

If these are portraits they are skewed ones; portraits of no-one and that is the point: being of no one person they are, at the same time, portraits of every person – of what rather than who we are – the universal rather than the particular. They are timeless; like the ancient bodies dredged from peat-bogs they emerge from their dark backgrounds squinting into the light of a world they did not see made and could never have imagined. The paint that simultaneously contains and creates these beings is itself peaty-rich; thickly layered and intricately manipulated it does not merely depict flesh but substitutes for it to give the viewer a visceral experience which is tactile and thought-provoking in equal measure.

The beauty of Kaufman’s images is precisely located in this shift beyond the confines of acceptable appearance. Like the self-portraits of Rembrandt in old age by which they were partly inspired, they fascinate at first by the very ambivalence their strangeness creates, and then by the growing awareness which closer inspection brings of the unconquerable being that sits behind the mask of the surface looking out. Beginning as judges, we may find ourselves being judged, and not necessarily by our own standards, a salutary as well as an unsettling experience.

Kaufman describes her paintings as more about the substance of the face than the likeness, but all the same each one has a clear, often haunting, individual identity that transcends conventional portraiture to touch the fundamental condition of being human; like us these are strangers in strange lands, living behind the masks we all choose to wear sooner than reveal our nakedness to the world. As spectators we look at them, and as we do so they look back: confrontational or questioning, anguished, suspicious or serene, but above all and inescapably one human being to another. These may not be not paintings about beauty, but they are beautiful paintings, full of the fascination of process and becoming, inviting us into a recognition of other dimensions to things we too easily take for granted or at someone else’s valuation. Paint is powerful stuff; in the right hands it can challenge our perceptions of even the most familiar aspects of our lives.

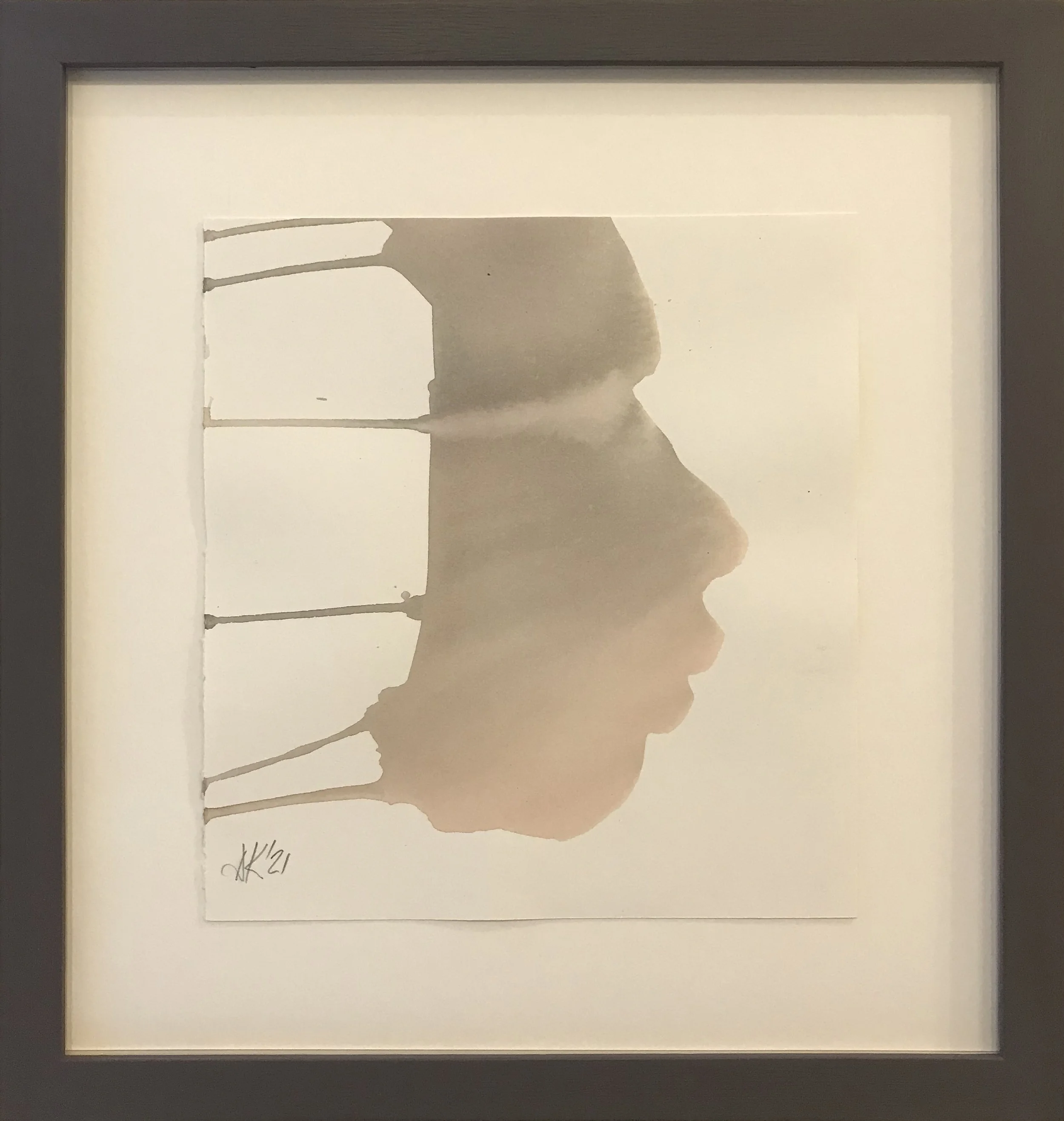

Works on paper